#1: Don’t Panic

Panic leads people to do things that seem reasonable in the heat of the moment, but may not be well thought out or reasoned and could have negative long-term consequences. Deciding that “all grains are evil” and embracing food fads is what got us here in the first place. If you are feeding a diet that is marketed as “grain-free” and it includes a number of newer pet food ingredients, such as chickpeas and lentils, and your dog appears otherwise normal at home (no changes to behavior, activity, appetite or stool quality) then take a deep breath and make an appointment to talk to your primary care veterinarian before changing the diet, because…

#2: Not all grain-free diets seem to be affected.

We (as in the larger veterinary community) are still in the early stages of figuring out exactly what is causing the recent cases of diet-induced DCM. We do know that not all diets that are marketed as “grain-free” are affected and that not all dogs or cats eating these types of diets go on to develop DCM. There was a recent webinar addressing this health problem and the three guest speakers (a veterinarian from the FDA, a PhD Veterinary Nutritionist who has been working with members of the pet food industry for decades, and a DACVN and PhD Veterinary Nutritionist who is probably the world-leader on nutrition and heart health) laid out the details of what we know to date. According to the FDA representative, they have received 149 reports of diet-induced DCM that include a total of 160 dogs and 8 cats (some of those affected are in multi-animal households, which only get counted as 1 report), with 39 dog deaths and 1 cat death attributed to this condition. If your dog or cat developed this preventable disease then any illness or death is an illness or death too many, but considering that at least as of 2015 pet foods marketed as grain-free accounted for about 1/3 of pet food sales in the US and are being fed exclusively to an estimated 20 million dogs and cats in the United States according to information presented on the FDA webinar, these cases would represent 0.00084% of the nation’s pet population being fed grain-free diets. Put another way that is fewer than 9 dogs and cats per 1 million dog and cats being fed grain-free diets as their sole source of nutrition and spread over the entire country. In all likelihood this problem is probably under-reported, but even if actual cases are 4x what has been reported that is still 0.0034% of the pet population eating grain-free foods. Don’t get me wrong, that number should be ZERO animals developing diet-induced DCM, but we need to keep some perspective. This problem has probably also been occurring since the onset of the grain-free pet food trend began 8 years ago, but it wasn’t until sales volume hit a critical threshold that a small percentage of animals having a problem with this type of diet became a larger percentage of the cases being seen by Veterinary Cardiologist that anyone began to notice. When it hit the mainstream media earlier this year, caregivers and the larger veterinary community began to take notice, too, but …

#3: Diet-induced DCM is not a new problem, unfortunately.

The first article confirming diet-induced DCM in cats was published in 1987 and a good overview of this condition in cats was published a few years later in 1992; taurine deficiency was identified as a contributing factor to DCM in Cocker Spaniels in 1997, in dogs fed low protein diets in 2001, and in a family of Golden Retrievers in 2005; and taurine-deficient canine DCM was seen in large breed dogs in the late 90s and early 2000s when these dogs were being fed certain commercial lamb and rice-based dry dog foods. The diet-induced DCM cases on lamb and rice diets spawned a number of additional studies and a sampling of them can be found here, here, and here. Larger companies and knowledgeable formulators knew about this potential problem and adjusted their formulas and recipe accordingly. Meaning if the pet food company was around in the early 2000s when the most recent wave of diet-induced DCM was seen or if it is a newer company that worked or continues to work with a Veterinary Nutritionist (either PhD or DACVN) and followed their advice on how to formulate and what to supplement, then the diet you are feeding is probably just fine, grain-free or not. But if you are concerned that your dog or cat’s diet might be a problem …

#4: Testing blood taurine levels is easy.

I am a huge advocate for preventative medicine in our dogs and cats. Our furry companions can look “healthy” from the outside and be harboring pretty bad disease on the inside. A number of my posts over the last few years are a testament to that. There are certain minimally invasive tests like blood draws or urine collection that can identify early stages of disease when diet, supplement, or medication intervention can have the most significant impact on health and longevity. If you are concerned about your dog’s (or cat’s) taurine status you can have your veterinary clinic collect blood samples and send them to the UC Davis Amino Acid Lab for analysis. The outside laboratories that veterinary clinics and hospitals use (Idexx and Antech) will also accept samples, but they are mostly just a conduit to UCD (for an additional handling fee) so I typically ship direct. Either way will work and if every dog eating a grain-free diet had whole blood and plasma taurine levels run it might help the researches get closer to a specific cause or causes for the current diet problems. Speaking of which, does everyone know that …

#5: Not all DCM is created equally.

Right now there are three categories of affected animals that veterinarians and researchers are seeing.

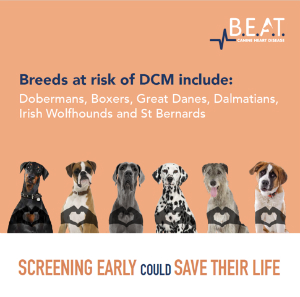

- Breeds that are genetically predisposed to DCM irrespective of diet, such as Golden Retrievers, Doberman Pinschers, Newfoundland, Portuguese Waterdogs, Irish Wolfhounds, and Cocker Spaniels. These breeds have an even higher risk of DCM if fed “high risk” diets. What were considered high-risk diets before the latest grain-free trend, you ask? Diets low in total protein; diets that included protein sources low in sulfur amino acid precursors (such as lamb-based, rabbit-based, and vegetarian or vegan diets); diets that are high in fiber that increases loss of taurine through the gut; or a combination thereof.

- Taurine-deficient DCM in atypical breeds. This and the third type of diet-induced DCM are the current areas of active interest. It is not clear if diets that are marketed as “grain-free” have other characteristics that are decreasing the bioavailability of taurine precursors (which are methionine and cysteine), or are changing gut bacterial populations to ones that basically chew up the taurine before it can get reabsorbed by the dog, or if there are anti-nutritive factors in the diet or individual ingredients that irreversibly binding taurine and prevent absorption/reabsorption. What we have seen is that companies supplementing both DL-methionine AND taurine or ones that have high inclusions of animal proteins and relatively low inclusions of plant-based proteins appear not to be involved with this problem, at least that we’ve seen so far.

- Diet-induced DCM not associated with taurine deficiency. This is the one that seems to be stumping researchers. According to the panel of experts on the September 4 webinar a small percentage of reported diet-induced DCM cases are in dogs that have normal plasma and whole blood taurine levels, but have still improved when the diet was changed and/or taurine was supplemented. This could be related to correcting of a relative deficiency in other essential nutrients with the diet change. An example of another non-essential in the diet, but essential for health, nutrient is carnitine. Like taurine, carnitine is essential for heart health, but unlike taurine, it also relies on another essential amino acid, lysine, for biosynthesis. Interestingly, lysine can be limiting in commercial pet foods in part due to the formation of Maillard reaction products. The Maillard reaction is the cross-linkage of lysine and sugars in the diet that occurs with heating (i.e. cooking) of a food that creates a physical browning reaction; it imparting a caramel color to cooked foods and a number of the aromas and flavors that make baked, roasted and grilled foods so tasty, but binding of lysine makes it unavailable for the animal.

The Take-Home Message

If your pup is seemingly healthy, doesn’t have any energy or appetite changes at home, and there are no clinical signs of disease on exam (no murmur or arrhythmia, normal ECG, no abnormal finding on a 3 view chest xray) then they can either stay on the current diet (assuming good quality manufacturer that is supplementing with any potentially limiting nutrients) or continue with a more complete workup including whole blood and plasma taurine levels and an echocardiogram before deciding the diet’s fate. It is not wrong to run whole blood and plasma taurine levels on a dog that seems “normal” from the outside and is on what appears to be a well-balanced diet if it gives everyone peace of mind, but it may not be necessary in all cases. Then once all test results are in you can decide whether a diet change is in order.

I don’t have a preference for brands or ingredients that caregivers feed (but please no raw!) as long as all of the essential nutrient needs of your dog or cat are being met and that diet is improving health and wellness. The field of veterinary nutrition has 50+ years of knowledge on how dogs and cats digest and metabolize whole grains, such as wheat, corn, rice, and barley, so unless your dog or cat has a specific allergy or intolerance to a particular whole grain, there is no reason to avoid them.

Happy (and Safe) Feeding!

Dr. Weeth and Miss Penny