Last week brought a revealing announcement from the FDA. After frequent and persistent petitioning from Veterinarians, Veterinary Nutritionists, and concerned Caregivers, the FDA finally released a list of the brands that have been linked to cases of diet-associated dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Since June 27, my inbox and social media sites have been blowing up with shares, retweets, and emails from concerned friends and family. The story was even picked up by major news outlets, like CNN and ABC, adding to the fervor.

But I’m conflicted about this report. On one hand, certain pet food manufacturers have taken a very cavalier approach to their diet’s role in this preventable and potentially deadly disease. Because only a relatively “small percentage” of dogs develop diet-associated DCM on their foods, they insist that there is no problem, ignoring the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. On the other hand, the FDA’s report paints a broad stroke over specific brands and is being interpreted (at least by the concerned friends and owners I’ve talked to) as an indictment of all “grain-free” or of certain manufacturers, which is a less than helpful oversimplification of a complex problem. As I advised in my post last fall (and this bears repeating here) I would urge caution before panicking and rushing to change your dog or cat’s food without considering what to change to. By all means if you are feeding a diet that has been associated with heart disease in other dogs then a change is warranted, but before jumping to another potentially problematic diet (just because it is not on the list) it is important to step back and look at what we know and don’t know to date.

Not a diet-associated DCM case, but could have been if we didn’t get him on the right diet for his breed and health status.

Recap of the Problem …

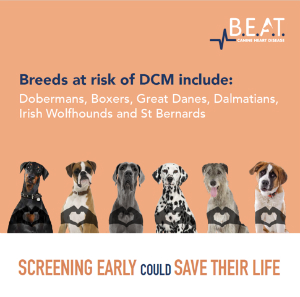

In 2017 Veterinary Cardiologists began noticing an increased incidence of DCM in Golden retrievers. This is a breed (along with other large breed dogs) with an increased risk of DCM in general, but the number of cases and age at onset of disease was not typical. This prompted a closer look at potential contributing factors and Veterinary Cardiologists then reached out to the larger veterinary community for information on other cases of unexpected or atypical DCM in any dog. Initially, the common thread was the feeding of a diet marketed as “grain-free.” Since that time the FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine (FDA-CVM) and researchers at both Tufts University and University of California, Davis, Veterinary Schools have been collecting data and working on finding a root cause of this potentially fatal disease. They have found that not only were Veterinarians seeing cases of DCM in dogs fed diets marketed as “grain free”, but also in dogs eating diets that use uncommon animal proteins (like kangaroo and bison, whether grain-inclusive or not) or that were made by smaller manufacturers that may or may not be adequately formulated for long-term feeding.

So what do we know?

- Not all cases are taurine deficient. Many of the dogs diagnosed with diet-associated DCM in the last 2 years had low taurine levels, but not all. Whether low or normal taurine levels were measured, most dogs if caught early had improvement in clinical signs and reversal of cardiac changes when their previous diet was stopped and taurine was supplemented.

- Not all dogs eating “grain-free” diets are affected. There are an estimated 20 million dogs eating diets marketed as “grain-free” that include some combination of legumes (peas, lentils, chickpeas, pinto, etc.) or potato (sweet or white), or both, and only (only?!) 515 reported cases of diet-associated DCM in dogs since 2017.

- Large breed dogs are at an increased risk, but even small dogs are affected. Large breed dogs account for 338 out of the 515 reported cases, but Shih tzus and Shetland Sheepdogs are on the list, too.

- Dry dog foods are the predominant type reported, but raw and home-cooked make the list, too. This probably has more to do with the relative popularity of these diet types rather than some inherent risk/benefit of a particular food type.

- “Grain-Free” is a marketing ploy and not based on any scientific or nutritional studies. There is no proven health benefit to avoiding grains in your dog’s diet unless they have a documented food allergy (which is actually very uncommon). Grains play a lot of roles in the diet, and most of these roles are pretty helpful at optimizing health.

What don’t we know?

- We don’t know the true scope of the problem. In people, underreporting of adverse drug effects is a well-known problem with some reviews indicating that as high as 95% of adverse reactions go unreported. Which means we may be seeing only the 5% of actual cases that were reported to the FDA and it could be closer to 10,000 dogs that are affected. It takes time to report a suspected adverse food event and Veterinarians and Caregivers may not realize the value of this reporting. Additionally, many owners may contact the pet food manufacturer if there is a problem rather than the FDA assuming that the information is getting relayed to the government agency.

- We don’t know where the problem is coming from. All grain-free diets are being targeted by media outlets and some enthusiastic pet “advocates”, but we don’t know if this is a problem with all grain-free diets (probably not), peas and legumes (maybe, especially at high amounts), and/or questionable formulations and manufacturing processes (probably, yes). When peas are included at relatively low levels in the diet (less than 20% of the total recipe) or as occasional treats they do not appear to cause a problem, but none of the diets from any of the brands on the FDA’s recent list have gone through controlled feeding and digestibility trials to prove that they are safe and healthy for dogs at the level of legume inclusion they use, which can be over 40% of the recipe when all types and portions are added up.

- We don’t know if this is an ingredient, dog, or manufacturer problem (or maybe all three). I suspect we will find that peas and potatoes in the hands of experienced formulators and experienced pet food manufacturers and for the majority of dogs are not the problem. The problem will be (like it was in the early 2000s when poorly formulated lamb and rice dog foods were causing DCM in dogs) a failure of certain manufacturers to account for variation in ingredient quality, changes in digestibility with processing, and individual variation in the dog population. Do affected dogs have low taurine production? Do they have increased loss from their gut? Do they have normal production and gut handling, but a low total food intake and are just getting inadequate intake overall? Meeting minimum nutrient levels on paper is not enough. Pet food manufacturers must know or hire knowledgeable individuals with an understanding for how nutrient levels vary in the raw materials, how they are affected by other ingredients or nutrients in the mix, the effect of cooking (or lack of cooking) on nutrient stability and bioavailability, and the wide range of variability in genetics and food intakes in the dog population. Basing diet formulations on market trends rather than nutritional science is a recipe for disaster.

- We don’t know if the percentages of the brands reported simply represent their popularity and market share or an underlying problem with these companies. Maybe the three most frequent brands reported are really no better or worse than the least frequent three brands, they are just better at marketing their diets so more people buy them. I don’t have access to those market insights to know whether this is true or not, but I bet these companies do.

At the end of the day, diet-associated DCM is a preventable condition and manufacturers who are selling foods that are labeled as “complete and balanced” have an ethical and fiduciary obligation to meet that label promise. Having an idea about pet foods, being a dog trainer/breeder/owner, inheriting a family pet-food business, and/or writing a book about dogs and cats (even if it’s about food) does not qualify a person to know what it takes to keep a large population of dogs and cats healthy. No free passes because you didn’t know what you didn’t know, no matter the sincerity, especially if it ends up with disease and death.

And if you are a Veterinarian who is seeing cases of suspected diet-associated DCM or are a Caregiver with a dog or cat who has been diagnosed with suspected diet-associated DCM, please report it by following the link here so we can help the FDA get to the bottom of this problem before more dogs and cats get sick.

Happy (and Safe) Feeding,

Dr. Weeth