Ah, the pancreas… an often overlooked and misunderstood part of the digestive system that only gets noticed by veterinarians and caregivers when it’s not working well. But the pancreas shouldn’t just get attention when it is inflamed and painful (from Pancreatitis), or not producing enough insulin (from Diabetes Mellitus), it deserves recognition for doing its job well and not causing problems on a day-to-day basis. Today’s post is to familiarize you with the pancreas and (hopefully) give you a few tips to help you keep it happy for years to come.

Happy Pancreas = Happy Dog

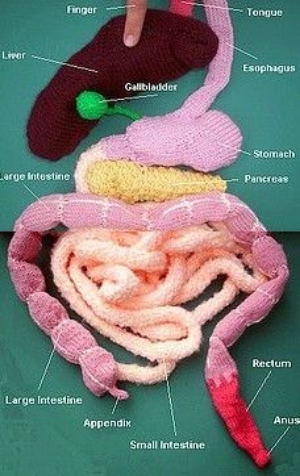

Anatomy of the Pancreas

This part gets a bit technical, so bear with me. The pancreas is a glandular organ that sits behind the stomach and extends across the length of the stomach to the upper small intestinal (the duodenum). It connects to the duodenum via the pancreatic duct, which serves at the pathway for release of digestive enzymes and other essential compounds into the intestinal tract. This part of the pancreas’ job is called its exocrine function. This is in addition to the pancreas’ other, probably more familiar role, the production and release of insulin into the blood stream (i.e., its endocrine function). The endocrine pancreas will be covered in my next post on Diabetes Mellitus; I’m not completely ignoring that topic, just pushing off for now.

Pancreatic enzyme release is triggered by the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) that is secreted from the intestinal cells in response to the intake of certain food components, specifically protein and fat. Both protein and fat will stimulate CCK release, but fat has a much more pronounced effect even at lower intakes. Irrespective of trigger, the secretion of CCK causes the pancreas to contract and squeeze pancreatic enzymes down the pancreatic duct and into the duodenum to begin the breakdown of dietary macronutrients (macronutrients = dietary protein, fat and carbohydrate). There are a few other functions of CCK, such as stimulating contraction of the gall bladder and creating a feedback on the brain to slow food intake, but it’s CCK’s effect on the pancreas that I am focusing on for management (and minimization) of pancreatitis.

Your key digestive organs, without the actual blood and guts

The Exocrine Pancreas

The primary exocrine enzymes produced by the pancreas are trypsin and chymotrypsin (both used for protein digestion), lipase (required for fat digestion), and amylase (essential for starch digestion). These enzymes are produced in their inactive forms, which must be activated by other enzymes in the presence of bicarbonate (also made in the pancreas). For example, trypsin is actually made and stored in the pancreas as trypsinogen. Trypsinogen is packaged into zymogen granules within the pancreas and kept separate from bicarbonate. This isolation of enzymes and activators protects both the integrity of the digestive process and the pancreas itself. If trypsin becomes activated too early not only will it not get into the duodenum where it is needed for food digestion, but it will start to digest the proteins in the pancreas instead. And this is painful. Very, very painful.

One of my former patients on IV nutritional support, fluid support and pain meds because of severe pancreatitis.

What Causes Inflammation of the Pancreas?

The clinical name for inflammation in the pancreas is pancreatitis (pancreas- = pancreas + -itis = inflammation). Pancreatitis can either be acute (vomiting and pain within hours) or chronic (low smoldering illness with vague signs that can be confused with other medical conditions).

In dogs, one of the most common dietary causes of acute pancreatitis is eating a non-food item (like 2 lb of bird seed) or eating fatty table scraps (either intentionally fed or found by rooting through the garbage). The exact mechanism of pancreatitis isn’t known but it is believed that the higher than normal fat intake causes the rapid increase in circulating blood fats and then “activation” of pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas. Other risk factors for acute pancreatitis include being a miniature Schnauzer or Yorkshire terrier (sorry pups), or any other dog breed that has a genetic predispositions to hypertriglyceridemia (the term for high circulating levels of triglyceride in the blood); being on medication such as potassium bromide and phenobarbital (two common anti-seizure medication); and being more than 20% over your ideal weight (yep, being a fat dog isn’t a cosmetic issue). Chronic pancreatitis in dogs is a bit more challenging to identify as the clinical signs can be vague and are often confused with other chronic medical conditions, because of this chronic pancreatitis is thought to be an under-diagnosed and under-reported condition. One study out of the UK conducted post-mortem evaluations of 200 dogs that had died from a variety of different causes (none of which were reported to be either acute or chronic pancreatitis in the medical records by the way) and found evidence of chronic pancreatitis in one-third of them.

Cats on the other hand like to be different. Genetics, medications, obesity, and high fat meals are not often associated with pancreatitis in cats. Instead stressful events, like introduction of a new animal into the household or having work done at your home, seem to be the more common histories among cats that present to their veterinarian with signs of acute pancreatitis. Many of these cats may also be diagnosed with what veterinarians like to call triaditis, (triad- = three + -itis = inflammation), meaning they are found to have evidence of inflammation in the pancreas (pancreatitis), in the liver (hepatitis), and in the intestinal tract (enteritis) all at the same time. Chronic pancreatitis can also be seen along with diabetes mellitus in cats, though just like with triaditis it often becomes a chicken-or-the-egg game to figure out which came first.

What Does Pancreatitis Look Like?

Animals, both dogs and cats, with mild cases of pancreatitis may vomit, refuse food, or seem quieter than usual at home. Dogs and cats with chronic, low-grade pancreatitis may have vague signs such as an intermittently poor appetite and weight loss. Severe pancreatitis can cause not only vomiting, food refusal, and lethargy, but diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain. Severe pancreatitis, if left untreated, can also result in shock, circulatory collapse, and death. So pancreatitis is basically badness, followed by more and more severe badness if not caught and treated.

Signs of pancreatitis aren’t always obvious.

What Can We Do About It?

Supportive treatment for dogs and cats with pancreatitis is very similar: IV fluids to keep them hydrated, anti-nausea meds to stop them from vomiting, and pain control (whether they are acting overtly painful or not) will be on the list. Dietary therapy on the other hand is less consistent so here is where I’d like to provide some general guidelines to caregivers, vet techs, and veterinarians when treating dogs and cats with known or suspected pancreatitis.

The two most important features of a diet for an animal with pancreatitis are (in order of important): 1) feeding a diet that is LOWER in fat than what was being fed before and 2) feeding a diet that is MORE digestible than what was fed before. If you don’t know what is causing the GI signs you’re seeing and you have pancreatitis as one of the possible causes on the list, err on the side of caution and just feed a lower fat, more digestible diet. Seems straight forward but I see a lot of confusion in practice about how to translate this to an actual diet so I give you…

Dr Weeth’s Dietary Consideration for Feeding Animals with Pancreatitis

What is in that bowl is as important as the rest of the medical treatment

- Dietary fat is a wonderful thing for healthy animals, except when it’s not. Fat can enhance the palatability of the food (I much prefer half and half in my coffee to skim milk); in the right amounts and with the right fatty acid profile can improve coat glossiness and decrease shedding (and big dogs can shed a lot!); fat also provides more calories per gram than either protein or carbohydrates, so feeding a higher fat diet relative to a moderate or low fat diet will increase energy density, reducing the overall volume of food needed each day; and with this reduction in volume in, so, too, do you see a reduction in the volume of poop coming out. The end result of feeding a higher fat food is often that the dog or cat readily eats their food, has a lovely shiny coat, doesn’t shed very much, and has a low stool volumes. Sounds perfect (and a lot like the reasons people give for feeding raw … hhmmm… maybe it’s not the “raw” part of those diets that is doing anything?…). Perfect unless you are a dog or cat with pancreatitis. When the pancreas is inflamed dietary fat can stimulate CCK release, contraction of the pancreas and release of digestive enzymes… into the pancreas. This promotes continued autodigestion of the pancreas and surrounding tissues, malabsorption of nutrients, and pain. Cats and dogs with abdominal pain can be very stoic, but if you or a human loved one has experienced pancreatitis you know it is not fun. Fat is sometimes your friend, but sometimes your dog or cat’s worst enemy.

- Digestibility is important for everyone. In general, over-the-counter (OTC) adult maintenance dog and cats food will be less digestible than the therapeutic intestinal support diets sold by veterinarian. This means that more of the OTC diet you feed (yes, even the “premium” priced ones) becomes poop rather than getting absorbed by your dog or cat. There is some variability in OTC diets and a number of the newer “premium” marketed foods, especially ones that are frozen/freeze-dried raw or fresh pasteurized, can be as digestible as intestinal support diets. BUT, before you think that sounds like a great option for animals with pancreatitis, many OTC diets (especially “premium” marketed foods), will have fat contents that exceed 50% of the calories in the diet. These types of diet would be very harmful for a dog with a history or an active case of pancreatitis. OTC diets marketed as “light” or “lean” will have lower fat contents compared to standard adult maintenance foods, but as the fat dropped in OTC diets, so does the digestibility. What about home-cooked foods you may ask? Some combinations of home-prepared foods, like cottage cheese and white rice or chicken breast and white rice, can be as digestible, if not more digestible, than the therapeutic intestinal support diets, but there is going to be a lot more variability depending on the way they are cooked and specific ingredients selected. Also, many home-prepared diets are rarely balanced for long-term feeding ( and if used should only be fed during the recovery stages of pancreatitis (about 2-3 weeks) before your dog or cat is transitioned to a balanced diet whether it is a commercial diet or you have the home-prepared foods balanced for long-term feeding.

- Diet History is key to finding the right diet the first time around. Whenever possible the decision of what to feed and the degree of fat restriction needed should be based on the previous diet intake. This is where diet and treat history are very important. Did your dog (that lovable furry fiend) get into the BBQ remains or a container of bacon grease you’ve been meaning to throw out? In these types of case your dog could have eating a whoppingly high fat intake and as such feeding a moderate fat contenting diet (one that provides between 20-35% fat calories) would be fine. Or did they develop pancreatitis or hyperlipidemia, or both, while eating a diet that was already at 25% fat calories? In this situation, feeding a diet with a similar fat content would not help, and could potentially make them worse. These dogs should be fed a diet that provides less than 20% of the calories from fat. Basically, you want to find out how much fat the dog is eating now and decease it by about half while still staying above the minimum requirement for fat. As I mentioned earlier, cats are a bit different and you want to find a diet that manages whatever concurrent medical conditions your veterinarian finds. Fat triggers and subsequent fat restriction are less important in most cases, but (and I feel like there is always a but) this is not true 100% of the time. I have definitely seen cats in practice that acted more like fat-responsive pancreatitic dogs and needed to fed a highly digestible, fat restricted diet.

The optimal long-term diet choice for a dog or cat with pancreatitis will depend on the inciting cause (genetics, medication, hypertriglyceridemia, or high fat intake) and additional medical issues (diabetes mellitus, IBD, etc). Irrespective of underlying cause, dogs with a history of pancreatitis should never be fed diets or treats with more than 45% of the calories coming from fat due to the risk of recurrent pancreatitis.

Happy and Healthy Feeding!

Lisa P. Weeth, DVM, MRCVS, DACVN